Google Doodle celebrates Japanese American author Hisaye Yamamoto (山本久恵), among the first Asian Americans to get post-war national literary recognition, in honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month on May 4, 2021.

Hisaye Yamamoto was born on August 23, 1921, to Issei parents in Redondo Beach, California. She is most popular for the short story collection Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, first published in 1988. Her work goes up against issues of the Japanese immigrant experience with America, the disconnect between first and second-generation immigrants, as well as the difficult role of women in society.

On account of race-focused laws, Hisaye Yamamoto’s family had to move much of the time. Yet, as a teen she discovered comfort in writing, oftentimes contributing short stories and letters under the pseudonym Napoleon to newspapers that served the Japanese American community.

As a mainstay, Hisaye Yamamoto discovered solace in reading and writing since early on, creating nearly as much work as she consumed. As an adolescent, her excitement mounted as Japanese American newspapers started publishing her letters and short stories.

At first writing exclusively in English, Yamamoto’s recognition of this language barrier and the generational gap would soon become one of her essential impacts.

Hisaye Yamamoto was twenty years of age when her family was placed in the internment camp in Poston, Arizona. With an end goal to stay active, Yamamoto started announcing for the Poston Chronicle, the camp newspaper.

She began by publishing her first work of fiction, Death Rides the Rails to Poston, a secret that was subsequently added to Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, followed shortly thereafter by a lot more limited piece entitled Surely I Must be Dreaming.

Following the outbreak of World War II, Hisaye Yamamoto’s family was among the 120,000 Japanese Americans forced to migrate to Japanese internment camps. She started writing stories and columns for the camp newspaper at the Poston, Arizona, camp to stay active, yet the physical and psychological toll of the forced relinquishment of homes and businesses would be a frequent theme in her later work.

Hisaye Yamamoto momentarily left the camp to work in Springfield, Massachusetts, however returned when her brother died while battling with the U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Italy. The three years that Yamamoto spent at Poston significantly affected all of her writing that followed.

World War II concluded in 1945, shutting the internment camps and releasing their detainees. Following three years at Poston, Yamamoto and her family got back to Southern California, this time in Los Angeles, where she started working for the Los Angeles Tribune.

This weekly newspaper, planned for African American audiences and serving the Black community, employed Hisaye Yamamoto basically as a columnist, as well as an editor and field reporter. Drawing from her involvement with the internment camp, Yamamoto wrote about the complexities of racial interaction in the US.

A lot of what Hisaye Yamamoto learned and implemented in her writing expanded the reception of her work to incorporate non-Asian American audiences. Her writing usually focused on issues that separated early generations of Japanese in the US, particularly the desire of the immigrant Issei to protect their language while the US-born generation Nisei inclined toward osmosis through expressions of loyalty to the US and accepting the English language.

After appreciating a lot of critical acclaim in the late 1940s and mid-1950s, Yamamoto married Anthony DeSoto and settled in Los Angeles.

Hisaye Yamamoto’s stories are frequently contrasted with the poetic form, haiku. She has likewise been praised “for her subtle realizations of gender and relationships.” Her writing is sensitive, painstaking, heartfelt, and delicate, yet blunt and economical, a style that pays homage to her Japanese heritage while building up the contemporary appeal.

Hisaye Yamamoto wrote about the intimidation a Black family named Short was encountering from white neighbors in isolated Fontana. After the family died in an evident arson attack, she reprimanded herself for using terms, for example, “alleged” or “claims” to portray the dangers against the family.

Yamamoto would leave journalism after writing the 1948 story The High-Heeled Shoes: A Memoir, which focused on the harassment women are oftentimes exposed to. The next year, she would follow that up with Seventeen Syllables, which investigates the generational gap between Issei and Nisei. Her 1950 misfortune The Legend of Miss Sasagawara recounts the story of a girl at a migration camp idea to be crazy just to be uncovered as clear notwithstanding suppression by her Buddhist dad.

DeSoto died in 2003. Hisaye Yamamoto, who had been in poor health since a stroke in 2010, died in 2011 in her sleep at her home in northeast Los Angeles at 89 years old.

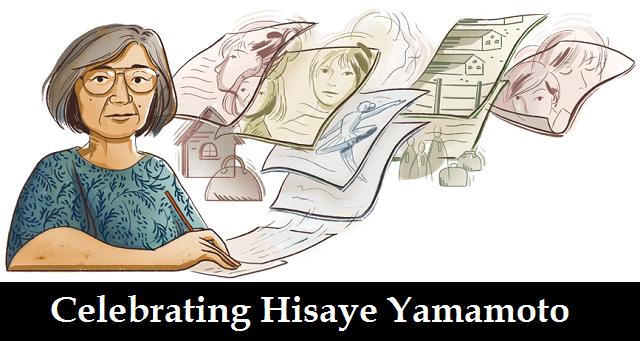

On May 4, 2021, Google showed up Doodle for Celebrating Hisaye Yamamoto to pay tribute to Asian Pacific American Heritage Month.

The present Google Doodle honoring Hisaye Yamamoto highlights representations of characters from some of her stories, streaming out of the pages that she’s writing on. On different pages, you can see some of the noticeable themes of her life and her writing, including a migrant lifestyle and a Japanese internment camp.

May is Small Business Month, a time to honor and recognize the achievements of the… Read More

Swiss International University (SIU) is on track to be one of the world's most respected… Read More

In a session that left students buzzing with fresh ideas and practical insights, Invertis University… Read More

At the 21st Shanghai International Automobile Industry Exhibition, which is surging with the wave of… Read More

Liverpool, UK—House of Spells and Comic Con Liverpool are once again collaborating to bring the… Read More

Introduction In India's booming EdTech space, there's one name that's making waves among Telugu students… Read More